Interview with Stephen CartwrightYun: When we are traveling about in the world, there are many ways to interact with so many new elements. We might see a difference in nature, people’s unfamiliar behaviors in a new culture, and different shapes of streets, cars, and houses. We can try foods and drinks that we have never before tasted. All of these experiences can leave sensuous memories on the body. Your work is interesting to me in terms of the lack of this kind of sensuous memory. You filtered data of your location, latitude, and longitude throughout your bicycle journeys around the world. I was really interested by the fact that instead of having a humanistic response that dealt with cultural interactions and experiences on these journeys, you chose a sort of quantifiable method to highlight the physical location of your body as opposed to what your body experienced. These numbers that you are using are the most de-textured and de-materialized outcomes that one might expect, and they go beyond the possible cultural interactions experienced on the journeys. As pure symbols, numbers do not have utterance. This makes me think that your work is not about viewing or experiencing, but about your body. With this in mind, I would like to talk about your methodology. |  Photo from Eurasian Odyssey 2003, http://www.crazyguyonabike.

|

Stephen: It is true that the main way of documenting my travels is by recording the data – latitude and longitude, distance travelled, elevation changes, etc. The process of making the recordings is simply remembering to turn on my GPS and mark the location. This hourly action causes me to pay attention to my place, and notice my surroundings. These recordings provide a consistent framework for the constantly changing scenery and experiences along a ride. It may seem cold and impersonal to record such rich experiences through numeric data, but for me it creates an unbiased diary of the experience. The numbers and locations educe vivid recollections that I can retrace neatly through time.

Yun: I would like to talk about your sense of the body, such as events that you can feel on your skin. While cycling, you wear goggles and other appropriate protections, like a helmet. These help protect you, but they must also limit your senses. What are you actually able to feel while riding? I see this as about "becoming a new human" by changing your body and function as a human whether you plan to or not. What do you want to be? What do you dream about through this work? Stephen: While riding a bicycle I am acutely aware of the environment around me. Subtle changes in wind and terrain can have profound effects on the effort needed to propel myself forward. On a bike you are experiencing the elements—sun, temperature, precipitation first hand and for extended periods of time. In settled life I don’t experience the world in the same way, it is too easy to keep yourself comfortable and easy to disregard the cycles of the natural world like the length of the day and changing seasons. The rhythm, repetition and pace of riding allows my thoughts to drift from the pressing matters that lie ahead to less tangible introspections. While riding sometimes I dream of just being in a comfortable place where I know where I will sleep and what I will eat next. Most thoughts are influenced by the immediate conditions of landscape,weather and fatigue but, when I am totally immersed in the ride I can dream of slipping into the world and rejoining the natural systems we find it so easy to overlook. In the sculptural manifestations of my work complex natural landscapes are broken down into more comprehensible sections or imagined from related collected data. They are another way to digest all the information that I experience/collect – quantifying landscapes and generating topographies out of data. |  Monfrague National Park, Photo from Eurasian Odyssey 2003, http://www.crazyguyonabike. |

Mass at Fatima, Photo from Eurasian Odyssey 2003, http://www.crazyguyonabike. | Yun: When traveling around by bike, you are in a different type of realm since you are traveling at different speeds compared to walking or driving. Biking is not the same as driving a car or flying in an airplane. You might feel the physical difference of flying, but it is not the same as cycling. While there is a rupture between locations and you feel several separate stages during flight, the location changes are not the result of one's own movement. As a driver of a car, the sense of the body is not topographical at all, though your body is shifted around as you sit in it. Biking, no doubt, offers you different types of bodily experiences. A bike has more intimacy with your body and you might remember actual distances and times that you spent to get from place to place. If our pets or children travel by airplane, they might not feel the journey itself. We understand what airplane travel means, but our body might not get it. What about your shifting body do you bring to your art work? How does the speed difference affect your sense of space and the shape of land? |

|  |

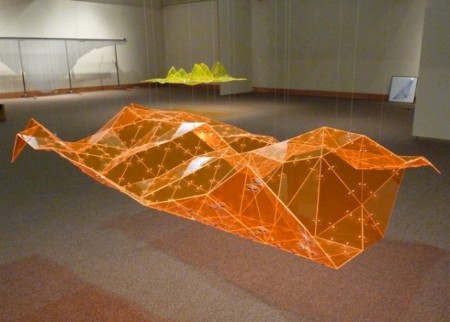

Mesh 1,2 (Cycling 1997-2009) Acrylic, 2010

Mesh 1 and Mesh 2 are based on running and cycling average mileage over the course of several years. Mesh lines running parallel to the front edge of the pieces plot a line graph of my average mileage over the course of a year. Variations in activity can be seen at certain times of the year, as well as year to year. Large peaks in Mesh 1 illustrate times of high cycling mileage while on self-contained bicycle journeys.

| Topologic Generator, Brass, aluminum, cable, plastics, motor, electronics, 88x42x67 in.2001 (modified 2007) This mechanism recreates the topography I experienced traveling by bicycle. In this version of the piece a landscape is rotated centered on Chamonix France. A stack of eccentric cams rotates moving levers that in turn move the intersections of telescoping brass rods to create the landscape. Only parts of the terrain I experienced first hand are used in creating the topography. In this instance information from bicycle tours in 2000, 2003 and other travel in 2001 generate the terrain data.

Stephen:Traveling by bicycle you have a much greater and immediate experience with the world around you, from the landscape to the people. Contrary to arriving in a new place by plane where everything is suddenly different, when you travel somewhere overland, by bicycle the changes happen at a digestible rate. One place flows into the next and parallels and common threads are easily noticed. Occasionally things do change abruptly, but these become memorable ruptures in a smooth transition; they can be natural or artificial, from a border crossing to the edge of land and sea. |

When I started my latitude and longitude project I imagined the system as a regular grid over the surface of the earth. In a global grid all points are more or less the same, but in drawings from my latitude and longitude project, my movements are not equal or evenly distributed. They are dictated by landscape, history and convention. For example routes through mountains were probably first used by animals and over time adopted by humans with increasingly complicated modes of transport. My movements are also dictated by life in this age: the requirements of work, the dispersed family and wanderlust. Yun: Are you considering your body as bicycle? Or bicycle as your body?

Stephen: I have never considered it like that, I guess I would suggest it was more of an extension of my body – with a seamless interface between me and the machine. I have been riding for so long that it is second nature to be on the bike. Just as you can walk without consciously processing all the muscle movements, control of my bike is nearly subconscious. The mechanics of propelling and steering the bicycle don’t seem to linger in my mind but go directly from thought to action without my noticing. In another sense, even the posture of riding links you to the land you are traversing with the texture of the ground transmitted through the handlebars, pedals and saddle. | Champaign Mining, Acrylic, 9x9x10 in. 2009

This piece examines the first half year of living in a new city, with each layer of acrylic representing one week. As I record my position in a place a circle is cut from that layer, as holes overlap they become amorphous shapes. Holes from lower layers are re-cut in upper layers and added to the cuts from that week, so each layer depicts the cumulative spatial experience up to that time. |

"...I guess I would suggest it was more of an extension of my body – with a seamless interface between me and the machine. I have been riding for so long that it is second nature to be on the bike. "

Yun: You also record your longitude and latitude when you are not moving by bicycle. I think that, as a person who has had different types of topographical experiences and speeds, your state of pause can be different as well. When you stay in place or move without a bicycle, is it like a person who always needs to wear his glasses to see more clearly? Do you feel the lack of the function of the bicycle as if it were an organ? Stephen: When I first get back into a car after a long ride, I find the speed terrifying, in the sense of danger but also in the sense of missing what is going by too fast. For me, cycling is the perfect pace—slow enough to absorb my surroundings but fast enough to feel progress. Yun: What

about when you are walking around? Stephen: Sometimes I find walking maddeningly slow. I appreciate the incremental progress the bicycle affords a perfect balance between observation and progress. The speed of walking can be just below that comfortable equilibrium point where appreciation of my absorbing my surroundings starts to be frustrated by a lack of progress. Additionally, every step walking on level ground requires the same amount of effort, but momentum is built up in cycling allowing the effort to accumulate.

Yun: Some of your projects look like a focus on creating the specific senses that you might have during a journey, such as Topologic Generator(2001), Range(2010) and Light (2003, 2004, 2006). In these works, you are not only using the data to create a physical object, you also created ‘machines’, which is working on the senses directly. Especially for Light, you used the recording of sunrise and sunset in your location to decide the length of chimes. By combining the two elements that at first glance do not look related, the sound made by 365 chimes based on the length of day at your location over a one year period seems like the rhythm of the ecological experience of your body. So even though audiences might not understand the date-based experience, by listening to the organic structural sounds they might understand the ecological structure of the life. In this work, your body rhythm was functioning as an instrument, and the body was invested with the shape of chimes. In this view, I consider Champaign mining as this kind of work. However, comparing Topologic Generator (2001), and Range (2010), the objects that self-generate their shape, I think you are using your body and ecological rhythm of life as a functional machine for Light and Champaign mining. Are you considering your body is an ecological machine? How is your life, in terms of being a living thing, related to your art methodology? |  Off Surface,1998,Bicycle, aluminum, aircraft fabric, 6x25x14 ft

Bike/plane constructed after return from a 4500 mile cross-country bicycle journey in the middle of the first year of recording my hourly latitude and longitude. The plane has functioning control surfaces but was never successfully flown. Light (2003, 2004, 2006), Aluminum, motors and mixed media, Dimensions variable (each set approx. 24x7x1 ft.), 2007

Since 1999 I have been recording the time of sunrise and sunset at my location. The 365 chimes in each set are cut to length based on the length of day at my location over a one year period. Changing latitudes, longitudes, elevations, time zones and seasons alter the local time of sunrise and sunset. Any deviation from a simple sine-like curve in the chimes indicates that there was a change in position on the surface of the Earth. The erratic nature of the 2003 chime set results from a year of almost continuous travel by bicycle and other means. |

Stephen: I couldn’t make my work without paying attention to the way I live. I record data and realize the reality of my life is different than my perception of it. I have to consider my body an ecological machine in two ways. First, that I am simply one of billions of organisms on the planet and my existence is not important in the grand scheme of things. But, secondly, I inhabit this body, in this time and place and it is the only consciousness I know. My work recording aspects of my life is an attempt to prove that I am here.

Yun: You mean, by using the analog recording system and a by-hand process, you can successfully remember or experience the differentiations of the data. Then it would not only be about recording via GPS. It seems that you are trying to recognize the meaning of the data by body accumulation processes.

Yun: You are living in Urbana, a relatively flat farmland area in central Illinois. Do you think the less dynamic topography of this area affects your senses?

09/12/2011

Since 1999 Stephen Cartwright has recorded his exact latitude, longitude and elevation every hour of every day. Cartwright uses digital and traditional fabrication techniques to translate his collected data into his sculptural projects. Since the inception of the Latitude and Longitude recording project Stephen Cartwright has completed several grand bicycle journeys through North America, Europe and Asia, totaling more than 20,000 miles. Prolonged observation of his location has led Cartwright to his recent work investigating the use and alteration of the landscape. |